Any person facing a sentencing hearing should learn the basics of the US Sentencing Guidelines. An understanding of the guidelines can help a person prepare for leniency. The resource below will offer insight that a person can use to work more effectively with counsel.

- iTunes Podcast, Episode 1 on US Sentencing Guidelines

- iTunes Podcast, Episode 2 on US Sentencing Guidelines

- iTunes Podcast, Episode 3 on US Sentencing Guidelines

Background:

I’m Michael Santos, founder of Prison Professors. On behalf of our entire team, we encourage all justice-impacted people to learn how the system operates. The more a person knows, the better a person can prepare for a better outcome.

Every member of our team learned many lessons by going through government investigations and prosecutions. We paid massive fines, and many of us served lengthy terms in prison. We strive to help others make better decisions and get better outcomes.

Today’s lesson offers insight into the basics of US federal sentencing guidelines. Any person facing a sentencing hearing should learn the basics of federal sentencing. We offer optional videos that provide additional commentary, and the links to other articles offer even more insight.

We hope our audience finds this information helpful in the quest to work toward the best possible outcomes.

- For sample of Guidelines Table / Loss Amounts / Calculators, visit this link.

- Article on Aberrant Behavior, and What You Should Know about Sentencing

- Article on Diminished Capacity and Preparing for Sentencing

Brief History of Sentencing Guidelines:

In the past, federal judges had enormous discretion when they considered what sentence to impose upon people convicted of crimes in federal court. In fact, when Judge Jack Tanner sentenced me, in 1987, the law provided him with discretion to impose a term anywhere between 10 years and life in prison. Without meeting certain factors, the law would not allow him to sentence me to less than 10 years, but he could sentence me to life.

In going through the sentencing process, I learned a great deal from the experience. In going through 26 years in federal prison, I learned a lot more.

We’ve built a team of subject matter experts, and we’ve worked with more than 1,000 people that faced sentencing hearings. Together, we’ve created a body of work that anyone can use to work toward a better outcome at sentencing.

Success in sentencing, like success in anything else, begins with the strategy we teach through all of our work:

- Step 1: We’ve got to define success as the best possible outcome.

- Step 2: We’ve got to document the strategy we’re going to use.

- Step 3: We’ve got to put our priorities in place.

- Step 4: We’ve got to create our tools, tactics, and resources.

- Step 5: We’ve got to execute our plan, holding ourselves accountable.

We encourage all people facing government investigations or criminal charges to learn more about the sentencing process. The more a person knows, the better a person can collaborate with counsel to advance possibilities for leniency at sentencing.

Remember that sentencing is only one component of the process. It’s an essential component, but the well-prepared person will engineer a pathway for success at every stage in the journey. Today’s lesson focuses on sentencing.

Indeterminate / Determinate Sentencing:

In the past, judges imposed indeterminate sentences in most cases. An indeterminate sentence means that the sentence a judge imposes doesn’t necessarily correlate with the length of time a person serves.

Indeterminate sentences allowed people an opportunity to qualify for parole. In other words, a judge would impose a sentence. At some point in the future, a parole board would assess the person again. Members of the parole board would determine whether continued imprisonment served the interests of society, or whether the person should serve the remainder of the term in the community under conditions of parole—a supervised-release type of condition.

In the mid-1980s, a series of high-profile cases led to new tough-on-crime legislation, ushering in the era of mass incarceration. People objected when they read that a judge imposed a 10-year sentence, but a parole board let the person out after the person served two years.

Further, with judicial discretion, the sentence lengths varied. Judges in one jurisdiction might grant leniency, while a judge in a different jurisdiction might impose a severe sentence for a similarly situated person and crime. The Supreme Court made a series of rulings on sentencing matters, regarding both indeterminate sentencing and determinate sentencing. For example, in one case, the justices spoke about disparate sentences for defendants with “similar histories, convicted of similar crimes, committed under similar circumstances.”[1]

With many inconsistencies in sentencing, Congressional leaders took action. They pushed for “truth in sentencing” rhetoric, striving for more consistent sentencing with the federal sentencing guidelines.

Sentencing Reform Act of 1984

As a result of mounting pressure, Congress enacted the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 (SRA). The SRA established a new federal sentencing guideline system. The SRA established sentencing practices by creating the federal sentencing guidelines.

In the same Act, Congress also created the United States Sentencing Commission (USSC). The USSC would focus on promoting proportionality in sentencing and reducing sentencing disparities among those convicted of federal crimes.

The Sentencing Reform Act became known as “The New Law.”

1987 Sentencing Guidelines

The SRA authorized the new guidelines in 1984, but the new sentencing law did not take effect until November 1, 1987. Any conviction prior to 1987 would result in a pre-SRA indeterminate sentence, known as “The Old Law.” Any conviction after November 1, 1987, would fall under the purview of the SRA, exposing the person to a guideline sentence.

Besides changing factors such as eliminating the parole board, and reducing the amount of credit that a person could earn by avoiding disciplinary infractions in prison, the SRA provided strict guidelines, with narrow ranges. For the most part, if a judge imposed an SRA guideline sentence, the person would serve close to the length of time the judge ordered.

The 1987 sentencing guidelines created “determinate” sentences that many judges deemed to be unfairly rigid. Some judges objected, feeling as though the new guidelines emboldened prosecutors to make decisions by the way they charged a defendant. Indeed, some judges rejected the guidelines and waited for the Supreme Court to determine whether the guidelines met constitutional standards.

In my case, the judge that sentenced me ruled the SRA and guidelines unconstitutional. He believed that Congress overstepped its bounds by appointing the United States Sentencing Commission. As a judge, he believed that the Constitution endowed him with powers of sentencing. The Supreme Court disagreed, making the SRA the law of the land.

The guidelines, as they were initially drafted, removed discretion from federal judges. Those guidelines imposed a relatively narrow range, in accordance with a formulaic table. That table has evolved over time, but it offers far less discretion than existed prior to the SRA. Further, as stated above, the SRA removed eligibility for parole and lowered the amount of credit a person could earn through good behavior.

Factors a Judge Considers at Sentencing:

According to the guidelines, a sentencing court considers seven factors when determining what sentence to impose. A sentencing court must consider:

- The nature and circumstances of the offense and the criminal history of the defendant;

- The need for the sentence imposed—considering four primary purposes of sentencing:

- retribution,

- deterrence,

- incapacitation, and

- rehabilitation;

- The kinds of sentences available (whether probation is prohibited, etc.);

- The sentencing range established by the sentencing guidelines;

- Any relevant “policy statements” promulgated by the Commission;

- The need to avoid unwarranted sentencing disparities among defendants with similar records who have been found guilty of similar conduct; and

- The need to provide restitution to any victims of the offense.

In our experience of working with more than 1,000 people that have faced sentencing, we would argue that judges treat the sentencing guideline factor as the most important of the seven factors. A person facing sentencing should understand this reality. By understanding more, a person becomes more qualified to engineer a mitigation strategy that may influence a judge’s decision.

Based on our conversations with scores of federal judges, two of whom appeared on video for our YouTube channel:

- Watch my video interview with US District Court Judge Bennett

- Watch my video interview with US District Court Judge Bough

We’re convinced that every defendant has a duty and a responsibility to build a record that would persuade a judge to consider more than the criminal charge—and to show why the person may be a worthy candidate for mercy.

For all the problems the Federal Sentencing Guidelines purported to solve, it also created new problems.

As a person that began and finished a 26-year journey through the criminal justice system, I learned many lessons that I want to pass along to others. When I began serving my sentence, I fell under the Old Law. I watched as judges began to implement the New Law. Since then, the sentencing laws have gone through many iterations. Changes have brought benefits to people being charged today—at least as contrasted to people that faced sentencing in the earliest stages of the SRA.

US v. Booker

Eighteen years after Congress enacted the federal sentencing guidelines, the Supreme Court ruled the mandatory sentencing guidelines were unconstitutional.[2] According to the Booker court, sentencing judges used facts not presented as evidence to the jury to impose maximum prison sentences. As a result, the legal standard applied to the facts was not the same as the facts the juries considered (beyond a reasonable doubt).

As a result of the Booker case, the federal sentencing guidelines do not have the same authority. Judges now have more flexibility to evaluate cases—and defendants—on their own merits. This change brought enormous hope and led to further reforms.

Another important outcome from Booker is the requirement that the sentencing judge imposes a “sufficient, but not greater than necessary” sentence to meet the purposes of sentencing. Theoretically, sentencing judges should impose the lowest sentence possible that still meets the purpose of criminal sentencing.

In our experience, however, a defendant has a lot of work to do. A defense attorney may make an argument on why a person may warrant leniency. Yet every individual must rely upon critical-thinking skills to advance his candidacy for leniency.

In our view, a person should approach sentencing as if he is about to make the biggest sale of his life. He is striving for mercy, for liberty. With such high stakes, he should prepare. For that reason, we create and massive amounts of resources to help.

Offense Levels

The first step in applying the federal sentencing guidelines is to select the guideline for each conviction. The USSC provides a statutory index that lists the guidelines applicable for most federal crimes. In other words, those involved compare the offense to the statutory index to locate the applicable guideline.

If the exact federal crime is not listed, the USSC instructs probation officers, prosecutors, and judges to use a guideline that they consider the “most analogous” offense. If a discrepancy exists between the offense listed in a plea agreement and a conviction, those involved should use the more serious crime to determine the sentencing range.

A defense attorney, of course, may present a case showing what he or she believes to be the appropriate guideline for crimes not specifically covered.

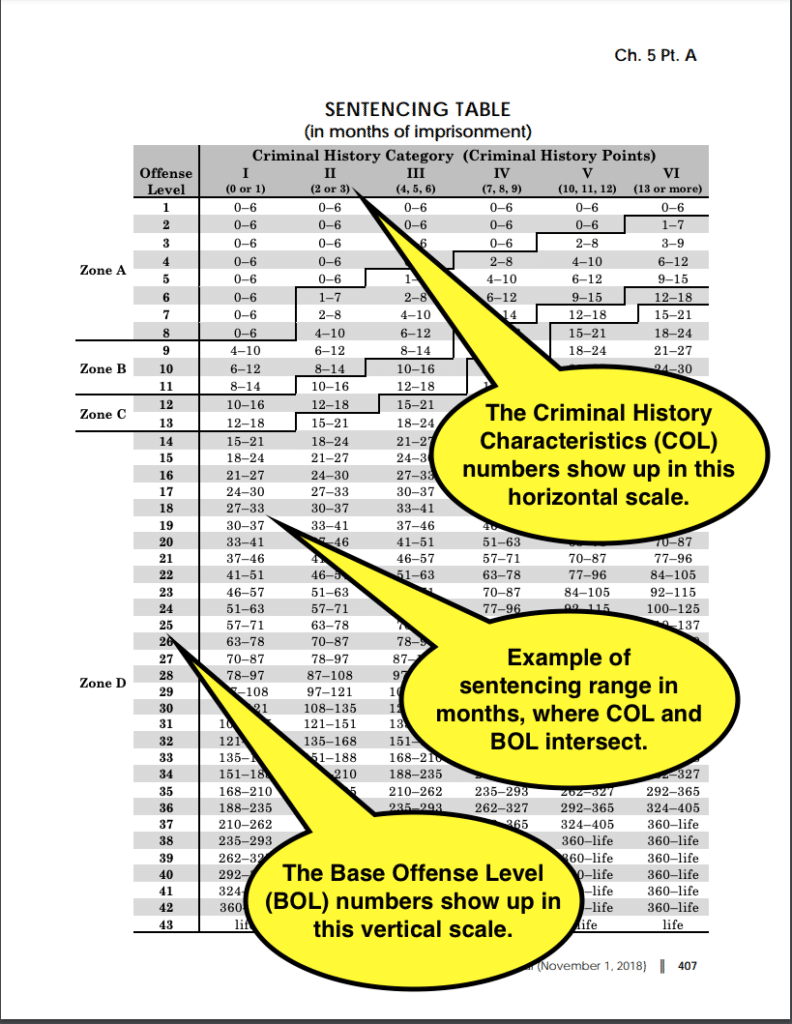

The guidelines generate a sentencing range. The determining factors include a “base offense level” and “criminal history.” Each of those factors includes a score that shows up on a grid with an X- and a Y-axis, known as the Sentencing Table. The base offense level (BOL) reflects the seriousness of the crime charged and shows up on the Y-axis (vertical axis). The criminal history characteristic (CHC) reflects the number of prior convictions for the defendant, showing up on the X-axis (horizontal axis).

The point on the table where these two axes intersect provides the sentencing guideline range. Although no longer mandatory, a sentencing court must consider this range before issuing a sentence. The judge will make a finding during the sentencing hearing on the appropriate guideline level. After the judge makes a finding, the judge may choose to depart downward or upward from the sentencing range.

Base Offense Level

A review of the crimes committed by the defendant determines the Base Level Offense (BOL). The BOL does not consider any facts specific to the case or defendant.

The USSC created a list of offenses and they assigned a specific level to each offense. For example, embezzlement carries a BOL of seven. Yet other factors, called sentencing enhancements, will also influence the range of sentencing (see below for a further description of enhancements and other factors that judges consider.)

Criminal History Characteristics

The guidelines require judges to consider a person’s past criminal history. The USSC assigned a series of points that appear on the horizontal access. Those points represent the number of prior convictions. A good defense attorney should understand this point system; probation officers and prosecutors will rely upon the guidelines to argue in favor of a severe sentence. For example, they will apply points as follows:

- One point for any prior sentence

- Two points for each prior sentence of at least 60 days

- Three points for each prior sentence of at least 13 months

Prosecutors add additional points if the defendant committed the crime while on probation, on supervised release, imprisoned, on work release, or if he was on an “escape status” from a term in prison.

Prosecutors and probation officers will count all convictions of less than 13 months for 10 years after the conviction. If the original sentence was longer than 13 months, prosecutors and probation officers will count the offense for 15 years.

CHC lies on the X-axis of the Sentencing Table and consists of six separate categories. Category I applies to people with no criminal history or one point. People who fall into Category I do not have much of prior criminal history. These people may have a lower guideline range compared to people who were convicted of the same crime, but with previous convictions.

If a person has an extensive criminal history, he will face a guideline range in Category VI of the axis, with much higher exposure to prison.

Specific Offense Characteristics

Probation officers, prosecutors, and judges also consider Specific Offense Characteristics (SOC) when evaluating where the conviction falls within the Sentencing Table. These additional “aggravating factors” typically consider the effects the defendant’s crime had on the victims.

Some examples of SOCs for white-collar offenses include:

- Whether the defendant abused a position of trust with the victim,

- Whether the crime created financial hardship, and

- Whether the defendant created more than ten victims.

Probation officers and prosecutors will consider dozens of SOCs when advancing arguments to impose a harsher sentence. Likewise, a person facing sentencing should build a strong case to show why he is worthy of mercy.

Using the crime of embezzlement as an example, the BOL is seven. One potential SOC is the amount embezzled. The guidelines provide for a 14-level enhancement if the defendant stole $1,000,000. The amount stolen will influence the BOL. In this example, the defendant’s Offense Level becomes 21 after applying the SOC.

Sentencing Guideline Range: The intersection of CHC and Base Offense Level

The sentencing guidelines provide a sentencing court a “range” in terms of months applicable to a criminal conviction. Several factors determine the range where the intersection of criminal history meets the base offense level.

The process starts with a pre-sentence report (PSR) prepared by the probation office. The prosecutors and defense attorneys discuss the PSR and may make adjustments. Finally, the PSR goes to the sentencing court for use in the sentencing hearing.

A person facing a sentencing hearing should understand the process of preparation, and how those preparations will influence the potential sentence. For example:

- Step 1: A defendant should invest time to learn about sentencing history, and strategy to influence a judge’s decision.

- Step 2: A defendant should document a strategy he or she will use to build a case for leniency.

- Step 3: A defendant should anticipate what the probation officer will say in the PSR and what the prosecutor will say at sentencing.

- Step 4: A defendant should work deliberately to make the best possible case for leniency—this cannot be boilerplate, but must be specific to the individual.

- Step 5: A person should understand what transpires at sentencing:

- A judge will go over discrepancies in the PSR.

- The prosecutor will argue why he believes the judge should castigate the offender. Then, the defense attorney will make an opposing argument.

- A judge will make a finding on every discrepancy between the prosecutor and the defense attorney—in most cases, expect the judge to side with the prosecutor.

- After the judge makes a finding on the appropriate guideline range, the judge will listen to an argument by the prosecutor on the government’s recommendation.

- Then, the judge will ask the defense attorney to make an argument, and the defendant may present his own argument.

Zones A – D on the Sentencing Table

As a result of several Supreme Court rulings, judges have more discretion to depart from guideline ranges. For that reason, our team cannot emphasize strongly enough the importance of preparing before the sentencing hearing. Each person needs to create a personalized, mitigation strategy. That strategy should advance the candidate for leniency. Our websites and YouTube channels offer an abundance of free information to help people learn. We recommend investing time and energy to learn how some people get non-custodial sentences, even though prosecutors and probation officers ask for years.

- No one is more important to a judge than the defendant. For that reason, a defendant should not expect the defense attorney to do all of the work.

- If a person wants leniency at sentencing, the person should work hard to earn liberty at the soonest possible time.

- Effective mitigation strategies require a person to build tools, tactics, and resources to help the defense attorney argue for a lower sentence, and to help the person build self-advocacy initiatives that will benefit him or her later in the process

The Sentencing Table’s offense level has four zones – A through D. To determine which zone a convicted defendant’s sentence falls into, the probation office, the prosecutor, and the defense attorney add the BOL, CHC, and SOC. While the parties may consider mitigating or aggravating factors, the offense level will fall into one of the four zones.

Zone A offenses tend to be lesser offenses that may be punishable by probation, home confinement, or community confinement (halfway house).

Zone B offenses are also lesser-type offenses but are within the recommended prison guideline range. For zone B offenses, defendants may receive a prison sentence and probation, home confinement, or time in a halfway house.

Defendants with Zone C offenses have a higher offense level and are more likely to receive prison sentences. These defendants may also receive a split sentence. A split sentence means the defendant will spend some time in prison but will also receive home confinement, community confinement, or some form of probation.

Zone D offenses are unlikely to receive probation as part of their sentences. Defendants with zone D offense levels usually are sentenced to prison terms of 12 months or more.

Grouping of Guideline Sentences

When convicted of more than one crime, prosecutors combine the convictions for sentencing purposes. By making combinations, they determine which offense level applies on the Sentencing Table. A defense attorney, of course, may argue in favor of the defendant; expect prosecutors to ask for more severe sanctions.

Courts use one of two ways to combine the offense levels. The first is grouping. The second involves using the most serious conviction and adding levels.

Prosecutors only group crimes when they are “closely related” to one another. For example, prosecutors may group one count for wire fraud with mail fraud if they’re related to the same underlying offense. Courts typically use grouping in white-collar convictions.

When the court does not group the offenses, it may use the most serious conviction and then add additional levels for the other crimes. For example, prosecutors calculated one count for murder and one count for bank robbery separately. The court then combined each of these offense levels to reach the sentence.

Departure / Variance

Again, the sentencing guidelines provide only recommendations. But the Court will likely also consider aggravating and mitigating circumstances to determine a starting point. People should expect prosecutors to define success with a longer sentence. For that reason, they should work to build a persuasive case for leniency. They should provide clear documentation to back up the argument. Theoretically, courts impose sentences that are “sufficient, but not greater than necessary” to meet the sentencing goals. In reality, the decision a judge makes may be subjective. The judge will determine what is “greater than necessary.” Again, the defendant should calculate steps he can take to advance prospects for leniency.

When the legal community discusses “variances,” they refer to sentences below or above the sentencing guideline range not supported by a departure.

The sentencing guidelines provide several factors that may support a departure, and others that judges should not consider, such as gender, religious belief, upbringing, and alcohol or drug dependence. The defendant must learn about these departures and variances, and create a strategy, with tools, tactics, and resources that advance prospects for a favorable outcome.

The sentencing guidelines encourage downward departures in the following circumstances:

- The victim provoked the defendant’s offense

- Avoidance

- Coercion

- Aberrant behavior

- Diminished mental capacity

- The defendant voluntarily admitted to the offense.

The sentencing guidelines also encourage upward departures in the following circumstances:

- Extreme conduct by the defendant

- Unlawful restraint or kidnapping

- Extreme psychological injury to the victim

- Endangering the public welfare.

Additionally, the guidelines discourage any departure for the following factors since they are common among all defendants:

- Age

- Education

- Skills

- Physical, mental, or emotional condition

- Civic and charitable contributions

- Employment record

- Family ties and responsibilities.

Additionally, prosecutors may grant the defendant a recommendation for a downward departure if he cooperates with the government to prosecute or investigate another offender. The prosecution must file a motion with the court indicating the defendant provided “substantial assistance.” Prosecutors create a potential hurdle for defendants when they reveal the defendant’s cooperation did not amount to “substantial assistance.”

Defendants facing this hurdle can request prosecutors to file the motion, but prosecutors rarely work to make things easier for a person charged with a crime.

Guilty Plea & Acceptance of Responsibility

One of the last factors to determine the defendant’s offense level includes consideration for acceptance of responsibility. After completing any other adjustments, prosecutors review the case for application of this potential downward adjustment. Typically defendants receive a two-level reduction for pleading guilty.

An additional one-level reduction can occur when he accepts responsibility for his crimes. Defendants must meet three conditions to qualify:

- The BOL must be level 16 or higher

- The defendant must notify the prosecution of his intent to plead guilty timely

- The prosecutor must file a motion indicating the defendant qualifies for this level reduction.

Acceptance of responsibility does not guarantee a reduction in offense level. Prosecutors refuse to file the motion for an additional reduction when convicted defendants change their plea or fail to follow through on other commitments.

Additional Adjustments 3553(A):

After judges make a finding on the guideline level, they consider factors outlined in Title 18 USC §3553 (A). Those factors include:

- The circumstances and nature of the particular offense;

- The specific defendant’s characteristics and history;

- The necessity of avoiding unwarranted differences amongst sentences for defendants convicted of similar conduct who have similar criminal records;

- The societal need for the sentence imposed;

- The kinds of sentences available;

- The importance of providing restitution to any victims, if applicable;

- Any relevant policy statement released by the Sentencing Commission (who writes the Sentencing Guidelines) that is in effect on the date of sentencing (except in cases of re-sentencing, which are more complicated).

Conclusion:

I’m not a lawyer. Although we work with many lawyers, we view our strength in offering personal experiences.

In my case, I’m a person that made horrifically bad decisions after my arrest. Despite knowing I was guilty, I chose to go to trial. In making that decision, I failed to consider how my lawyer’s interests may have diverged from my interest. When he told me to leave everything in his hands, and not to research or think about sentencing matters, I should have been suspicious of his motivations.

- My bad decisions put my liberty on the line.

- More bad decisions exposed to a sentence that was far longer than I would have faced if I had prepared better.

We encourage people facing criminal charges to listen, learn, and ask questions. Facing a sentencing hearing presents significant challenges. As we say, a person should prepare as if he or she is about to make the biggest sale of his or her life. Learn as much as possible, and prepare extensively.

If you have further questions about your personal circumstances, or the options available to you, consider joining our private community. You can learn more about our private membership community, by clicking the link below:

[1] Koon v. United States, 518 U.S 81 (1996)

[2] United States v. Booker, 534 U.S. 220 (2005).